DOROTHEA TANNING

Women artists. There is no such thing or person. It's just as much a contradiction in terms as 'man artist' or elephant artist'. You may be a woman and you may be an artist; but the one is a given and the other is you.

Il est difficile d’aborder la carrière de Max Ernst sans s’arrêter sur celle de Dorothea Tanning. Peintre et muse, elle forma avec le maître du genre « le couple le plus extraordinaire du surréalisme » pendant près de trente-quatre ans.

Alors qu’Ernst se rend dans son studio New York sur les conseils de sa dernière épouse en date, Peggy Guggenheim, il tombe immédiatement amoureux de cette artiste mystérieuse. Son autoportrait, Birthday, où la peintre s’est représentée en fée surréaliste, poitrine nue et regard perdue au loin, subjugue Ernst.

«Au début, il n'y avait qu'un seul tableau, un autoportrait. Une toile de taille modeste au regard des standards actuels», se souvenait Dorothea Tanning. «Mais elle remplissait tout mon studio de New York, une pièce située à l'arrière de mon appartement, comme si elle avait toujours été là. D'un certain point de vue, le tableau racontait le lieu: j'avais été frappée, un jour, par la multitude fascinante de portes - hall, cuisine, salle de bains, studio- ainsi regroupées, attirant mon attention avec leurs plans antiques, leur lumière, leurs ombres, leurs ouvertures et leurs fermetures imminentes (...) C'était la période de Noël, et Max fut mon cadeau de Noël. Il neigeait dur lorsqu'il sonna à la porte. Il venait choisir des tableaux pour une exposition intitulée Thirty Women, émissaire chargé de dénicher dans les ateliers un bouquet de peintres qui se devaient être jolies et aussi déterminées à être artistes. “Please come in,” Je souris, essayant de dire la formule comme à n'importe qui d'autre. Il hésita, restant le pied posé sur le seuil (...) Nous entrâmes dans l'atelier, sur le chevalet était le portrait, inachevé. “Comment allez-vous l'appeler?”, me demanda-t-il. “Je n'ai pas de titre”. “Alors, vous l'appellerez Birthday”. Cela s'est passé comme ça».

Werner Spies, spécialiste de Max Ernst, raconte : «Quand Max a vu Birthday, il est resté médusé devant son invention formelle, l'orage dans ses yeux peints de Cassandre qui contenait une profonde prémonition du désastre, son jeu de portes qui ne s'ouvriront jamais ou ne se fermeront jamais, une idée qu'a reprise Dali dans le rêve surréaliste qu'il a dessiné pour Hitchcock dans Spellbound. Il a quitté Peggy, s'est installé avec Dorothea qui était une beauté digne d'Hollywood et d'Autant en emporte le vent. Longtemps, Peggy Guggenheim en garda rancune et disait à propos de ces Thirty Women, «il y a une peintre de trop!». À la Biennale de Venise en 1966, vingt ans après, elle invita Max et Dorothea au Cipriani lors d'un dîner de pseudo-réconciliation qui fut des plus sinistres. [...] C'était une femme, non seulement belle, mais extrêmement poétique. Elle a souffert, à son retour aux Etats Unis après la mort de Max, d'être un peu ignorée. Elle avait vécu à l'ombre d'un grand artiste, était sophistiquée comme une Européenne, refusait le féminisme qui faisait la loi dans le monde des artistes alors à Manhattan. Son œuvre en a pâti. »

Née en 1910 au sein d’une famille suédoise vivant à Galesburg, dans l’Illinois, Dorothea entreprend des études d’art, passionnée par le dessin.

En 1930, elle quitte sa famille pour Chicago puis fréquente un temps l’académie of Arts Institutes. Elle s’installe par la suite à New York où elle gagne sa vie comme dessinatrice publicitaire. C’est en visitant l’exposition des surréalistes et dadaistes au MOMA en 36 que Dorothea a l’idée de devenir peintre. En 1942, elle se joint au groupe surréaliste de New York sous la direction d'André Breton.

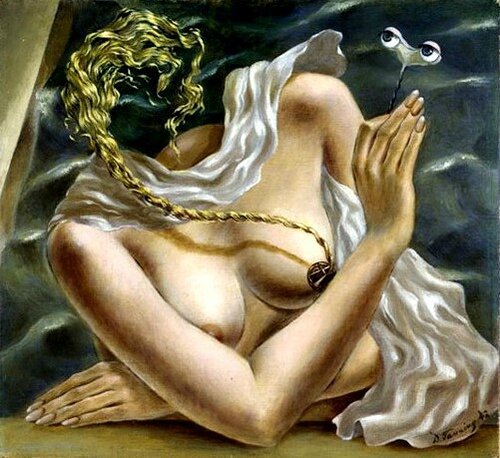

L’originalité de Tanning réside dans son renversement de la perception érotique dans l’art. Ses peintures osent exprimer les fantasmes de la femme, en lui redonnant sa place d’individu à part entière et plus celle de simple projection du désir de l’homme. En effet, les femmes qui gravitent autour des surréalistes sont presque toutes liées aux peintres en tant que muse ou épouse et correspondent avant tout aux critères esthétiques et mentales du mouvement : ce ne sont pas des femmes « comme il faut », bonne mère et épouse fidèle, mais elles doivent être belles, fascinantes, disponibles et sans inhibitions.

Dorothea s'éteint à l'âge de 101 ans. Elle était la dernière mémoire du surréalisme.

Une interview donnée dix ans avant sa mort, l'article entier à lire ici.

At the age of 91, how do feel about carrying the surrealist banner?

I guess I’ll be called a surrealist forever, like a tattoo: “D. Loves S.” I still believe in the surrealist effort to plumb our deepest subconscious to find out about ourselves. But please don’t say I’m carrying the surrealist banner. The movement ended in the ’50s and my own work had moved on so far by the ’60s that being a called a surrealist today makes me feel like a fossil!

Surrealism must have had a strong appeal for you at the time.

When I saw the surrealist show at MOMA in 1936, I was impressed by its daring in addressing the tangles of the subconscious — trawling the psyche to find its secrets, to glorify its deviance. I felt the urge to jump into the same lake — where, by the way, I had already waded before I met any of them. Anyway, jump I did. They were a terribly attractive bunch of people. They loved New York, loved repartee, loved games. A less happy detail: They all mostly spoke in French. But I learned it later.

You came to New York to be an artist in the midst of the Depression — just got on a bus one day from Chicago — with no plan and without knowing where you would stay. I don’t imagine there were many young woman doing that. Did you see yourself as a pioneer?

Not a pioneer but headstrong. Now when I look back, I’m amazed at my stupid bravery, going off like that with just $25. My head was full of extravagances, I’d read Coleridge and a lot of other 19th century dreamers and I had to be an artist and live in Paris. So New York was on the way. I finally got to Paris, just four weeks before Hitler started his March. Americans were told to go home; I went to my uncle’s in Stockholm on a train with Hitler Youth. I got the last boat out of Gothenburg in September of 1939. In 1949, I went back to France and stayed there for 28 unbelievable years.

You write in your recent memoir that, even in those days the art world was “a kind of club based on good contacts, correct behavior, and certain tactical chic.” How chic were you in those days, Ms. Tanning?

Chic! I didn’t have any money to throw away on frivolities. I wore discount $5 dresses from a wonderful place on Union Square called Klein’s. Also thrift shop stuff. A few of us took to wearing old clothes, but they had to be really old, from another time, way back. We’d show up in these rags as if it were perfectly natural. You had to be deadly deadpan about it. One of these appears in my painting “Birthday.” It was from some old Shakespearean costume.

Well, excuse me for this, but “Birthday” is among other dreamlike things, a topless self-portrait. Is it fair to say that at that time, 1942, people thought you were immodest?

Well, I was aware it was pretty daring, but that’s not why I did it. It was a kind of a statement, wanting the utter truth, and bareness was necessary. My breasts didn’t amount to much. Quite unremarkable. And besides, when you are feeling very solemn and painting very intensively, you think only of what you are trying to communicate.

So what have you tried to communicate as an artist? What were your goals, and have you achieved them?

I’d be satisfied with having suggested that there is more than meets the eye.

In your memoir, you advise pretty girls who want to be artists to get ready for a lot of frustration. How frustrated were you?

I don’t want to give the impression that I was a beauty. Just the same, I always noticed a curious reaction as if there were something unnatural about a really nice-looking girl doing something dead serious. It may be different today. Or maybe there are more pretty girls.

Is there any specific advice you can give to artists and writers cursed with good looks?

Yes. Keep your eye on your inner world and keep away from ads and idiots and movie stars, except when you need amusement.

I imagine you have struggled with the label of being a “woman artist” as well as the “wife of” Max Ernst, who was a founder of surrealism and a seminal figure in 20th century art. Would things be different for you today?

Yes and no. You need fortitude and patience. This goes with a big dose of indifference to the art world; you absolutely need that indifference. If you get married you’re branded. We could have gone on, Max and I, all our lives without the tag. I never heard him use the word “wife” in regard to me. He was very sorry about that wife thing. I’m very much against the arrangement of procreation, at least for humans. If I could have designed it, it would be a tossup who gets pregnant, the man or woman. Boy, that would end rape for one thing. And “woman artist”? Disgusting.

Many people have been using the word “surreal” to describe the events of Sept. 11th. The horrors of the world wars were a factor in bringing about dadaism and surrealism. Do you think artists will have a similar impulse now?

“Surreal” has become such a buzzword. There may be a need for something equally moving but certainly not for going back to something. Anyway, yes, there is certainly a need for hard and different thinking after what has happened and before what may happen.

But what kind of thinking? You’ve lived through the Depression and several wars. What is the role of art in such times?

Art has always been the raft onto which we climb to save our sanity. I don’t see a different purpose for it now.

What do you think of some of the artwork being produced today?

I can’t answer that without enraging the art world. It’s enough to say that most of it comes straight out of dada, 1917. I get the impression that the idea is to shock. So many people laboring to outdo Duchamp’s urinal. It isn’t even shocking anymore, just kind of sad.

As you mentioned, there was a lot of shock value in the work of the dadaists and the surrealists that you fell in with. Was that somehow different?

In its beginning, surrealism was an electric time with all the arts liberating themselves from their Snow White spell. There is a value in shaking people up, meaning those who have forgotten to think for themselves. Shock can be valuable as a protest. Like the dada fomenters, sitting there in the Cafe Voltaire in 1917 — their disgust with the world they lived in, its lethal war, its politics, its so-called rationales. Shock had value at that time. But ideas and innovation will always prevail without any deliberate effort to shock.

What about folks like Dali, walking his lobster on a leash?

Dali used his silly shenanigans to get publicity, to which he was extravagantly addicted. He made some sublime paintings, he was a master painter and his exhibitionist tricks didn’t enhance him as a person or as an artist. It was a pity really.

What’s your take on recent controversies at the Brooklyn Museum: the “Sensation” exhibition, the elephant dung and the more recent Last Supper in which the artist portrayed herself, nude, as Jesus Christ?

The Brooklyn show was blatantly shock-hopeful. And our mayor took the bait like a fish. I probably would not have liked it any more than the mayor if I’d bothered to go.

Were you in favor of the Guiliani’s moral standards panel on art?

Hitler banned and burned “degenerate art.” Stalin did the same. I suppose they had their moral standards too. I can only say that if a work doesn’t make being sane and alive not only possible but wonderful, well, move on to the next picture.

We live in an age when so many people seem to want to be artists of some kind. Why do you think that is? And what does it say about our culture?

All these young hopefuls swarming the big city and getting nowhere fast; that’s such a sad thought. But if there has been a big surge in the number of people making art, it’s because our prosperity has released so many of us from need. It has allowed our creative impulses to test themselves without starving the body. Many people find joy in actually doing something the pragmatist would call useless.

We are also obviously living in a society that prizes youth. Has this larger cultural bias had any effect on you in recent years?

You are so right. Even old people want to be teenagers. But if my memory serves me well it wasn’t all that glorious. To my surprise, I have come to like being old. You can do what you want.

You have been friends with so many important cultural figures. May I ask you to play a little pseudo-surrealist free-association game? How about your husband Max Ernst?

His humor. Ironic, amused, bemused. We laughed a lot. Even today, I have to keep from finding things absurd, which mostly they are. At the same time I’m crying my eyes out.

How about André Breton, founder of surrealism and dadaism?

Severely: “Dorothea, do you wear that low neckline just to provoke men?”

René Magritte?

Sweet.

Truman Capote?

A neat little package — of dynamite.

Orson Wells?

Scowler.

Joseph Cornell?

The courtly love of the 13th century troubadours.

Dylan Thomas?

How could anyone resist his bardic exuberance, his dithyrambs?

Duchamp?

Peerless.

Picasso?

One time when I was at his house, Jhuan-les-pins, for an afternoon visit, we stood at the kitchen door yard for farewells and he broke off the last flower from an old rose bush and handed it to me. How would you feel?

James Merrill?

Best poet, best friend, best fun. He died much, oh much, too soon: seven whole years ago.

What are you working on now?

I still write poems. Not that I overestimate them, but it gives me such pleasure why deny myself? The other day I read a beautiful pair of lines by Stanley Kunitz: “I have walked through many lives/some of them my own.”

If you could change anything in your life, or lives, what would it be?

More color in my dreams.

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F49%2F41%2F1277032%2F133272095_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F77%2F03%2F1277032%2F133168507_o.jpg)

![THE PLEASURE SEEKERS / CRADLE [sisters quatro]](https://image.canalblog.com/01Z82qF0A3EqF7hPMRFZ3Yx_p38=/400x260/smart/filters:no_upscale()/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F24%2F75%2F1277032%2F133038605_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F67%2F06%2F1277032%2F131252729_o.jpg)